|

April 2023 marked the 25th anniversary of the signing of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. Queen's University Belfast was host to a series of events involving so many politicans, Prime Ministers, former Presidents of the USA and various ambassadors, dignitaries, academics and the lucky few who were able to get tickets. Over at QSS, we marked the occasion in our own way by showing a reconfigured version of The im/material monument; an exhibition which ironically, I had shown at Queen's University Naughton Gallery the year before. What has changed in a year? In twenty-five years? For me, personally and professionally, there have been so many changes, good and bad. What has changed for you?

March can wrong foot us. One day we are sitting outside in the sun watching the first buds and flowers emerge and the next, we are tentatively picking our way through ice and snow. We are between seasons. In Northern Ireland we can get all of them in one day. This March, I have been sowing creative seeds and hoping that some of them, if not all, will take root despite or indeed because of the environment in which they have been planted. Just as it is certain that the tide will come in and go out again, so it is true that we are always between things. Failure or success, rejection or acceptance, this and that. I have realised that rather than jumping between these polarities, exampled perhaps in the highs and lows of artistic practice, it is possible to exist in the liminal space of neither/nor. Neither land nor sea, salt spray or sand but something that defines its own edges and finds its own way of being true to its nature.

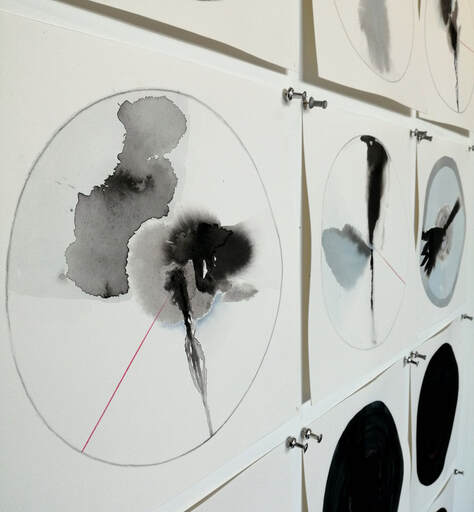

The year started as it ended - preoccupied with time. Using the circular form of the traditional clock face, I began experimenting with non-numerical ways of marking the time, in splashes and drips and floods of pigment. From the start of the series to the end, these studies progress from faint mark making to blocked out circles where no marks can be seen. Studying these, I reflected on how they were analagous to how we humans have left our mark on the earth - from barely a trace to virtual obliteration of anything that is sensitive to our presence. Reading around this led me to consider the Doomsday Clock where, in 2023, those involved in its calibration have calculated that we are now 90 seconds to midnight. In other words, the closest we have come (since 1947 at least) to wiping ourselves out by war, climate change, biological threats and disruptive technology. On this cheerful note (!) one can be optimistic and think that things can only get better but realistically, the best we can do is arrest time, or roll it back. In 1991, the Doomsday Clock was the furthest it has been from midnight at seventeen minutes, marking the end of the Cold War. As the days become perceptibly brighter and therefore longer, I hope we all have enough time to do the things we need and want to do and to make our mark lightly.

They say the proof is in the pudding and in December we can all eat too many of those! Here the proof, if any is needed, comes in the form of me - all robed up and striding across the stage of the Whitla Hall in Queen's mid-December on what was one of the coldest days of the year. Graduation is a surreal affair. Although family and friends can be present, often one does not graduate with one's peers and colleagues, as we all finish our studies at different times. I was delighted, therefore, that my friend and colleague Deirdre McBride was able to join me for a quick photo at the site of one of our common points of interest - where else but a WW1 memorial! I hope to reciprocate in June when (Dr) Deirdre graduates and hope that the weather is at least above zero. At first, December seemed a strange time for graduation but the more thought I gave to it, the more I realised how fitting it was, for me at least. A week after these photographs were taken, we had the Winter Solstice, then Christmas and New Year. It is a time of year which marks the end of things and signals the start of new beginnings and possibilities. For many, including me, 2022 was a year of highs and lows, of celebration and mourning and of saying goodbye to old friends. These photos mark not just the end of the PhD journey but a period of time in life which, of course, includes so many other things. So here's to 2023, drawing lines - figuratively and literally - and moving forward. Now that the shortest day is behind us, we can look forward to more light.

The Venice Bienalle can be overwhelming - a smorgesbord of sights, sounds and smells. I guess it has to 'go big' to be able to compete with the reality of Venice itself. At the Bienalle there are always new things to see and new artists to discover whereas wondering around Venice is like visiting an old but labyrinthian friend! Together, the combination of old and new, complemented by dark chocolate gelatos, aperol spritz and late autumn sunshine made for a rejuvenation of body and soul. Standouts for me were the late (great) Paula Rego, Anselm Keifer at the Ducal Palace and Rebecca Horn (tucked away in the main pavilion) as well as a peripheral show by Marlene Dumas at the Palazzo Grassi. There is too much to list but away from the still crowded Bienalle there is splendour to be found by wondering into old churches and abandoned buildings far away from the Giardini or Arsenale sites. Mosquitos aside, it was well worth the trip!

How has your summer been? Mine has been alternatively busy and filled with inactivity. I went to London in July and saw some great exhibitions, I went to Berlin too, and got covid. It seems there is no escaping it , no matter how hard we try. It made me think of the contrasts in our lives, from trying to fill every moment with activity to trying to find the time to be willfully inactive; to pause and just think. The image here shows one of my favourite places to sit, beneath the boughs of an ancient oak tree. In its shade, there is time to process, to reflect, to muse and ponder. To let your mind drift and come back to itself through birds singing and the sounds of the leaves rustling. As autumn approaches, a little early this year, and the leaves start to fall, I wonder what the next few months will bring and how I will approach them. How will you? Monuments are not just made in brick and stone. This ancient oak has seen it all, kept its powder dry and just slowly become more magnificent. Surely that can't be wrong!

June 2022 has been significant and busy in so many ways. I set up my exhibition "The im/material monument" in the Naughton Gallery at Queen's University, I passed my viva and had not one but two openings, followed by a presentation for an international colloquium on the future of counter-monuments organised by Leeds University. I think I am ready for a break, or at least a pause! The work shown above is a triptych called Elegies for the Dead of the Troubles. It was one of the most sombre pieces in the exhibition and it represents my re-imagining of traditional commemorative art. The language used is not of duty or sacrifice but of air, bubbles and hope; of movement and of breathing. As I acknowledge the personal sense of achievement I feel at the end of this month, and indeed of the whole PhD period, I also acknowledge that we are never out of Trouble and that for many people around the world, and for different reasons, hope drifts away. I hope that like the tide, it will come back.

Time can be thought of as a series of measured pauses that punctuate our waking hours. But these pauses are not always the same. For some people, time runs too fast and for others, it is always too slow. We wish we had more time to do our own thing, or to spend with someone we love or even to go back in time so that the future could be changed. If we think of time only as linear, numerical and regulated then these concepts remain in the realm of speculation and we are not reading time, or experiencing it, in the ways that we need to. How can we be fully in the present if we are pulled back to the past by the narrative of a history we do not subscribe to? How can we share a future if we can't move beyond the present because those with the power to change time cannot move beyond blame? Are we all too quick to blame and too slow to forgive, even ourselves? In the piece above, I went back in time to November 2021, when I reimagined time by drawing out an alternative clock-face. It was a way to think about time differently and to consider the temporal gaps between holding on and letting go. Now, the time seemed right to finish the work so here it is!

Time: A structure of nothingness. Mixed media. 45 x 45 x 5 cm. Photography: Simon Mills. What can be said about March - aptly named after the Roman God of War. It feels like the world, or parts of it at least, have gone mad and all we can do is watch from afar as another despot bestrides his part of the world fuelled by the delusions of grandeur. Meanwhile, people die and people mourn. I have been continuing my experiments reflecting on the shape of mourning and how it can be materialised to reflect its changing and uncertain nature. The bio-plastic petals I made in January were melted down and reformed into pebbles, each with their own unique markings. No two are the same and yet they share certain characteristics. They are hard, yet not fixed; set but vulnerble to the whims of their maker. I envisage these pebbles as a floor piece; a scattering of shapes. Some gather in numbers, some become separated and pushed to the side.; they may even be stepped on or over. How we shape our mourning is how we respond to the individual within the whole. The victims of war are not a homogeneous mass but a collection of myriad individual potentialities. This is what is lost. This is what we mourn.

This time last year I posted a photograph of the shore and reflected on how the year before I had been in Paris. Two years on, the world is still in a strange and increasingly dangerous situation. Monuments such as the Giant's Ring, shown here, are one of my touchstones in troubled times. They give a sense of continuity and timelessness when all around us is subject to change and uncertainty and the whims of mad men. For some reason, when I was here a few mornings ago, I thought of Joyce's The Dead, the last story in The Dubliners. It describes snow falling softly over Ireland, drifting over graveyards and hedgerows and " falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead" and I hoped that in other country, far from Ireland, enough snow would fall so that tanks were halted and planes couldn't fly.

|

AuthorThis is where you will find news about exhibitions, projects, events, other artists, travels, experimental work and sometimes things that I just enjoyed seeing! I hope you enjoy them too! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed